Why Most Audit Failures Start in the Mind

When corporate failures surface, post-mortems often blame weak controls, missed red flags, or poor governance. Rarely do we ask the uncomfortable but critical question:

How were auditors thinking when those risks were reviewed?

Audits are not just technical exercises. They are judgment-driven processes. Two audit teams can examine the same organization and reach vastly different conclusions—not because of data, but because of mindset.

Over the years, six recurring audit mindsets repeatedly show up across internal audits, statutory audits, forensic reviews, and board investigations. None are inherently flawed. But when one mindset dominates unchecked, it creates blind spots that history has repeatedly exposed.

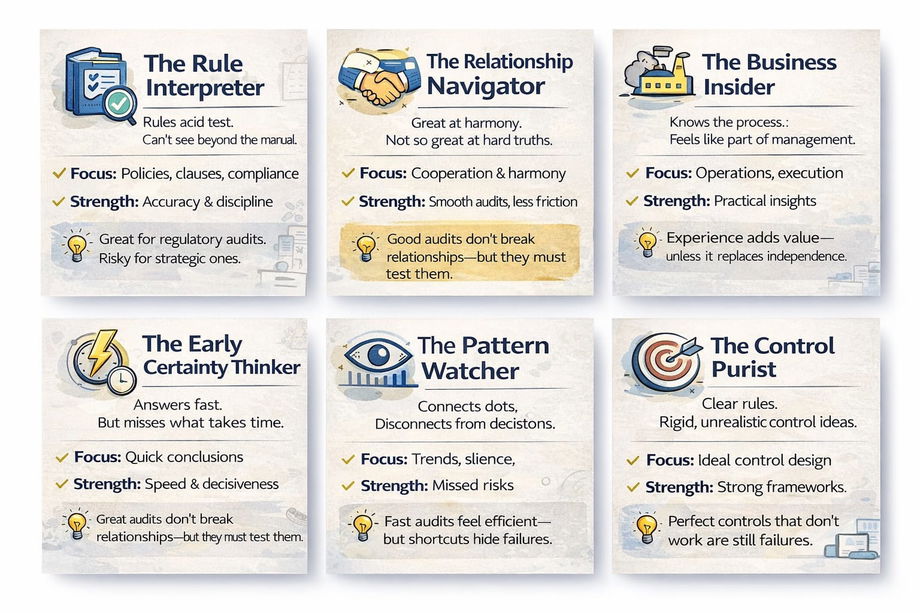

1. The Rule Interpreter

“If it complies on paper, it must be fine.”

The Rule Interpreter places deep trust in policies, documented controls, and regulatory checklists. Compliance becomes the proxy for effectiveness.

Strength

Strong regulatory alignment

Clear documentation trail

High confidence during inspections

Blind Spot

Confuses compliance with control effectiveness

Ignores behavioural override

Misses intent behind transactions

Ex: Satyam Computers

Before its collapse in 2009, Satyam appeared compliant on paper. Policies existed. Audit reports were clean. Financial statements followed accounting standards.

Yet, massive cash balances were fictitious.

Auditors relied heavily on documentation and confirmations without adequately challenging management representations or reconciling operational reality with reported numbers.

Lesson:

Rules were followed. Controls existed. But truth did not.

Key Insight: Paper compliance cannot substitute professional skepticism.

2. The Relationship Navigator

“Let’s not damage the working relationship.”

This mindset prioritizes harmony with management. Difficult conversations are softened, findings diluted, and conflicts avoided.

Strength

Cooperative audits

Easy access to information

Less resistance from management

Blind Spot

Avoids confrontation

Underreports uncomfortable findings

Gradual erosion of independence

Ex: Yes Bank (Pre-2020 Crisis)

In the years leading to its crisis, multiple warning signs existed—concentration risks, aggressive lending, weak recoveries. Yet, governance mechanisms failed to escalate concerns forcefully.

Auditors and committees maintained cordial engagement, but hard truths were delayed.

Lesson:

Comfort replaced courage.

Key Insight: An audit that never creates discomfort is usually not doing its job.

3. The Business Insider

“This is how business really works.”

Often former operators or industry veterans, Business Insiders bring valuable operational insight into audits.

Strength

Practical recommendations

Context-aware risk assessment

Implementation-friendly solutions

Blind Spot

Normalizes deviations

Justifies control failures as “business realities”

Gradual loss of independence

Ex: IL&FS

IL&FS was run by highly experienced professionals who deeply understood infrastructure finance. Over time, complex structures, rollovers, and funding gaps were treated as “temporary operational issues.”

Audits failed to challenge systemic risk accumulation because insiders understood why shortcuts were taken—and accepted them.

Lesson:

Experience became justification.

Key Insight: Understanding operations should sharpen skepticism—not replace it.

4. The Early Certainty Thinker

“I’ve seen this before.”

This mindset forms conclusions quickly, often based on prior patterns or initial observations.

Strength

Fast decision-making

Efficient audits

Confidence in judgment

Blind Spot

Incomplete evidence

Misses slow-burn risks

Overconfidence in intuition

Ex: Wirecard

In Wirecard’s case, early explanations for inconsistencies were repeatedly accepted. Each red flag was treated as a resolved issue rather than part of a growing pattern.

Auditors concluded too early that concerns were addressed, missing the scale of manipulation.

Lesson:

Speed replaced depth.

Key Insight: Fraud rarely reveals itself fully in the first signal.

5. The Pattern Watcher

“Something doesn’t feel right.”

Pattern Watchers focus on trends, silence, and anomalies rather than isolated transactions.

Strength

Detects emerging risks

Strong fraud-sensing ability

Cultural and behavioural insight

Blind Spot

Delayed conclusions

Difficulty converting intuition into findings

Risk of over-analysis

Ex: Enron (Early Signals Phase)

Before Enron collapsed, analysts and internal observers noticed recurring complexity, opaque disclosures, and consistent avoidance of clarity.

The signals were there—but not acted upon decisively.

Lesson:

Signals were noticed, but not escalated forcefully.

Key Insight: Seeing patterns is useless unless organizations act on them.

6. The Control Purist

“If the framework is perfect, risk is contained.”

The Control Purist believes strong design eliminates risk.

Strength

Robust governance frameworks

Clear accountability structures

Strong theoretical controls

Blind Spot

Overengineering

Controls detached from real behaviour

False sense of security

Ex: Wells Fargo Sales Scandal

Wells Fargo had extensive controls, policies, and compliance frameworks. Yet, aggressive incentives drove employees to open millions of fake accounts.

Controls existed—but human behavior bypassed them.

Lesson:

The system was perfect. Incentives broke it.

Key Insight: Controls fail when they ignore human pressure.

Why Audit Failures Are Usually Mindset Failures

Most audit methodologies focus on:

Scope

Sampling

Testing

Very few focus on how conclusions are formed.

Failures occur when:

One mindset dominates

Alternative perspectives are ignored

Judgment becomes predictable

Strong audits require deliberate balance.

What Boards and Audit Committees Must Ask

Instead of only reviewing reports, boards should ask:

Which mindset dominated this audit?

What viewpoints were missing?

Where did comfort override skepticism?

Where did speed override depth?

The Best Auditors Don’t Choose a Mindset

They manage all six.

Audit quality is not about intelligence or tools. It is about independence of thought, awareness of bias, and disciplined skepticism.

History shows us repeatedly: Controls fail first in the mind—long before they fail in systems.